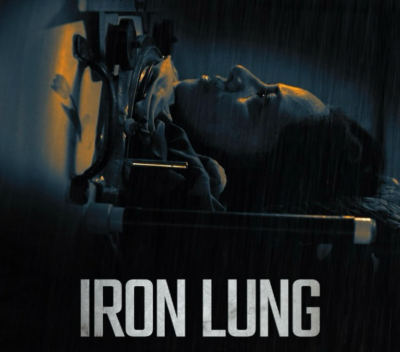

Polio. Iron lungs. These one-time commonalities from a bygone era play a central role in Director Andrew Reid’s short film, Iron Lung.

Polio. Iron lungs. These one-time commonalities from a bygone era play a central role in Director Andrew Reid’s short film, Iron Lung.

Set in New Mexico in 2002, and revolving around two sisters, Norma and Luisa Peña, the film opens on a shot of a darkened sky with heavy rain falling outside the window, flashes of lightning, cracks of thunder, and a radio announcing “record rainfall,” “flash flooding,” and recommendations to “shelter in place, and not attempt travel unless your life is in immediate danger.”

The camera pans, revealing a large piece of machinery accompanied by vaguely mechanical breath-like sounds. A cut shows an item resembling a magic wand jutting out from the end, gently tapping up and down on a laptop keyboard. The wand rotates vertically, and the edge of a face appears. Next, viewers see the face full-on, shown through a mirror, and a person – Norma – holding the wand in her mouth and maneuvering it around. A final wide shot reveals the machinery in its entirety: the titular iron lung.

Moments later, a flash of lightning and thunder, and the power goes out.

A different light turns back on, and another person – Luisa, Norma’s sister and caretaker – walks into the room and turns on a lantern. Norma asks, “How bad is it?” and Luisa responds, presciently, “Save your breath.”

Donning a bright yellow rain jacket, Luisa heads out into the storm to check on the generator as Norma gazes through the window. Luisa returns with bad news, “The generator’s gone, okay…We have no power.”

Without power, the iron lung is inoperable, meaning that Norma has “probably a couple of hours before her lungs give out.”

The rest of the film centers on this struggle: keeping Norma alive. And through this struggle, it accurately presents many of the experiences that disabled people face. Viewers witness the uncertainty of not only living but surviving as a disabled person.

From natural disasters cutting off individual evacuations, to snowstorms impeding ambulances, to health insurance refusing to cover essential medications, to healthcare provider skepticism resulting in mis- (or even non-) diagnosis, to managers denying requests for accommodations – all these things and more have a profound impact on disabled people that can range from inconveniences to threats to their very lives. And while just one thing going wrong in and of itself can be a big challenge, just like in Iron Lung ,things often compound.

This uncertainty is further highlighted by how viewers see Norma navigate this situation. She engages with autonomy in a way that will be all too familiar to anyone who has dealt with a disability or illness. She constantly has to rely on Luisa for a variety of tasks ranging from basic needs to ones essential for survival.

But even with this necessity of relying on her caretaker, Norma is depicted as neither hapless nor helpless. For example, in the very first scene, viewers see her utilizing the wand to operate the laptop, even from within the confines of the iron lung. She also displays her autonomy through the requests she makes of Luisa. It is her decision, not Luisa’s, to be taken out of the iron lung. Rather than being a mere bystander or plot point, she is an active participant.

Though all people are subject to things outside of their control, Reid’s film illustrates how disabled people are often subject to these things at an even higher level and how that leads to heightened uncertainty, particularly when things go wrong. Viewers witness an authentic depiction of disabled autonomy as something that is in some ways limited by and dependent on the actions of others, and how that autonomy shows up even amidst chaos and uncertainty.

The film also highlights the role Luisa plays as Norma’s caretaker, which exemplifies how to respectfully care for others. While performing tasks related to Norma’s survival are a no-brainer, Luisa also complies with other requests, even when she disagrees with them. Even when expressing her discontent, Luisa goes about it on the level of equals. She doesn’t approach her dissent from a paternalistic or condescending standpoint, avoiding any sort of “I know what’s best for you, so you should listen to me and do what I say,” mindset. Instead, she clearly expresses when she disagrees with Norma, but in the way that one would with any sibling or close friend. Every time Norma makes a request related to her own body, Luisa always helps her achieve it. Through these interactions, Iron Lung showcases how one can act as a caretaker respectfully, without falling into the cliché pitfalls of paternalism or savior complex.

While illness, disability, and disease have profound impacts, it is still possible for people who experience them to lead full and fulfilling lives. However, there is still fallout, both to themselves and to their loved ones. Reid shows that even so, it is important to respect their autonomy and see them without prejudice.

“As a filmmaker with a physical disability, I’m dedicated to reshaping the way disability is portrayed on screen,” Reid said in an interview with Disability Belongs™. “Iron Lung tells a story that audiences haven’t seen before, offering fresh, authentic disabled representation in a compelling and entertaining way. With recent successes like ‘CODA,’ ‘A Quiet Place,’ and ‘Ramy’ bringing authentic disability narratives into the mainstream, I believe Iron Lung is more timely than ever.”

Iron Lung will screen at 9:30 a.m. PT on February 22, 2025, as part of the 2025 Slamdance Film Festival in Los Angeles.